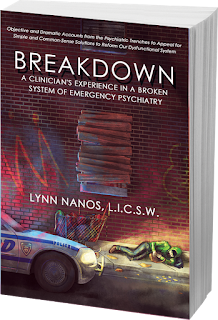

I finished reading Breakdown: A Clinician's Experience in a Broken System of Emergency Psychiatry, by Lynn Nanos. The opening page of Breakdown quotes Dorothea Dix: “…I come as the advocate of helpless, forgotten, insane, and idiotic men and women….” Like the Civil War era Dorothea, Lynn Nanos is a Massachusetts woman and tireless advocate for people with serious mental illness.

As a parent of a thirty-year participant in the mental health

system, I found Breakdown informative, comprehensive, well-researched, and thoroughly-referenced.

Practical advice and familiar vignettes weave through the narrative as only

someone who has been on the front lines of psychiatric emergencies can document.

Each of the twenty-two chapters is focused and does not shy away from difficult

issues or controversial positions. Nanos’ experiences as a clinician in

Massachusetts document the roles, laws, and regulations in that state as I ponder my state of Idaho. For instance, what is a Roger’s

Monitor in Massachusetts and how does this compare to Idaho? This is a court order for patients to receive antipsychotic medication regardless of whether they want such medication. Many people with mental illness do not adhere to treatment recommendations because they lack awareness of being ill.

Nanos tells stories of

individual crises, which she skillfully uses to document the complex problems

surrounding the personal and societal costs of mental illness. I am intrigued

by her ability to tell the stories of countless individuals from her perspective as a professional clinician in an urban setting. By

contrast, I am one family member, an artist and knitting machine educator by

trade, with one long story, in rural, north Idaho. My personal experiences

include every topic and every chapter in Breakdown,

supporting my daughter as best as I

can. My tenacious efforts have

partnered and often struggled with doctors, nurses, social workers, hospitals, living situations, guardianship proceedings, Social Security, Medicare,

Medicaid, the Department of Health and Welfare, law enforcement, Crisis Intervention

Team (CIT) police, and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

The complex mental

health system is far removed from Dorothea Dix’s advocacy efforts. But, how much

better off are people with serious mental illness, no longer shuttered away and

forgotten in insane asylums? Today medications replace straight jackets while

the Institutions for Mental

Diseases Exclusion law did away with 400-bed hospitals, which in turn

led to homelessness, violence, victimization, addictions, inadequate resources,

best-guess medication practices, revolving door social services, fatigued

families, and abandonment. What we have here is a multi-faceted “Problem Pile-Up.”

Geographic population densities

differ. Massachusetts has 839 people per square mile while Idaho has nineteen people per

square mile according to United States Census Quick Facts. A great source to

compare individual states is the Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC), which reports that in Massachusetts with a population of 5.5

million, 60,000 people live with schizophrenia. In Idaho with a population of

1.3 million, 14,000 people live with schizophrenia. The TAC statistics reference

United States Census statistics. Coincidentally, one percent of the population of

each of these states live with schizophrenia, which begs the question…where do

these facts originate? Are the solutions the same in both urban and rural

America?

While statistics and

anti-stigma campaigns are useful to start conversations, CIT may save lives,

NAMI classes educate family members, Mental Health Courts and Assertive

Community Treatment teams may restore some people to better lives, my humble

opinion is that these noble and worthwhile efforts are but band-aids on our

society which is bleeding out. No one sets out to be homeless, incarcerated,

hospitalized, die by suicide, or face an accidental early death. Policy makers need

the education to give priority to the people affected by serious mental

illness, the most difficult task. To be trite, an ounce of prevention is worth

a pound of cure. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. There is a giant

elephant in our living room and there isn’t a circus tent big enough to house

her ill body. Together, one bite at a time, with a dedicated commitment to

constancy, structure, encouragement, and acceptance, we can make changes that

would make Dorothea Dix proud.

I have yet to

personally meet authors Lynn Nanos, E. Fuller Torrey, Pete Earley, DJ Jaffe, Robert

Laitman and others. Their writings and advocacy work through books and social

media are enabling me to be a more knowledgeable advocate for my daughter and

other people who are so disabled that they can’t speak for themselves. I hope

that you will join our efforts!

Gini Woodward,

Mother of a fifty-year-old daughter with schizophrenia

Bachelor of Arts in Social Sciences

Past Experience:

NAMI Family-to-Family

Educator

NAMI family support

group facilitator

Idaho Region 1

Behavioral Health Board member and State Hospital

North Advisory Board member